Chapter 7: Stress

In this Chapter

Immediate Response

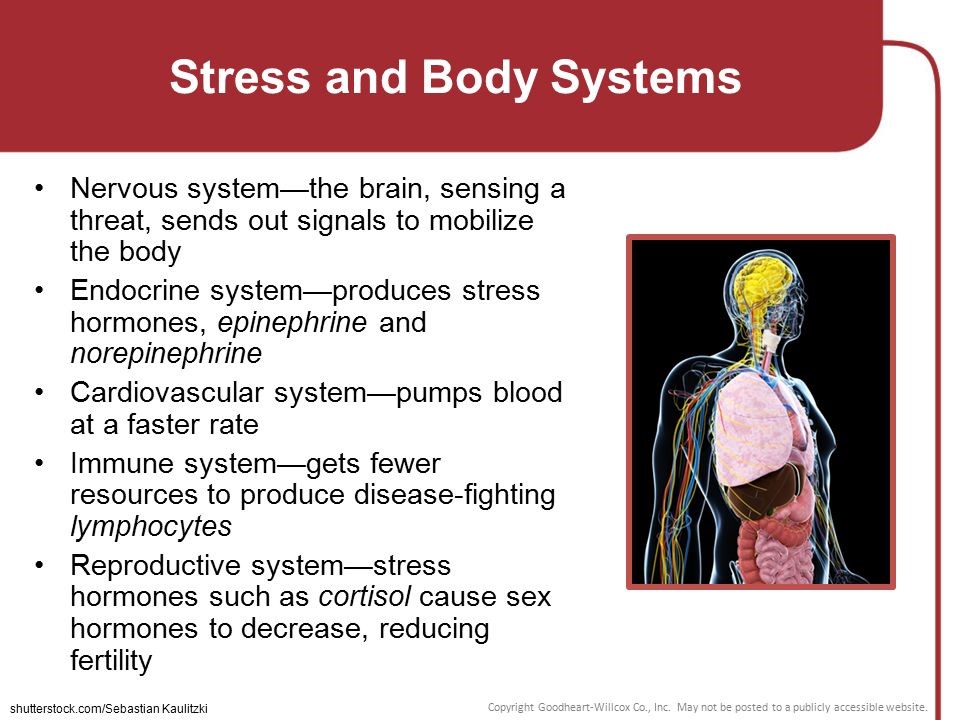

1A stressful situation activates three major communication systems in the brain, all of which regulate bodily functions. Scientists came to understand these complex systems through experiments, primarily with rats, mice, and nonhuman primates such as monkeys. Scientists then verified the action of these systems in humans.

2The first of these systems is the voluntary nervous system, which sends messages to muscles so that we may respond to sensory information. For example, the sight of a shark in the water may prompt people to run from the beach as quickly as possible.

3 The second communication system is the autonomic nervous system, made up of the sympathetic and the parasympathetic branches. Each of these systems has a specific task in responding to stress. The sympathetic branch causes arteries supplying blood to the muscles to relax in order to deliver more blood, allowing greater capacity to act. At the same time, blood flow to the skin, kidneys, and digestive tract is reduced. The stress hormone epinephrine, also known as adrenaline, is quickly released into the bloodstream. The role of epinephrine is to put the body into a general state of arousal and enable it to cope with the challenge.

4In contrast, the parasympathetic branch helps regulate bodily functions and soothe the body once the stressor has passed, preventing the body from remaining in a state of mobilization too long. If these functions are left mobilized and unchecked, disease can develop. Some actions of the calming branch appear to reduce the harmful effects of the emergency branch’s response to stress.

5The brain’s third major communication process is the neuroendocrine system, which also maintains the body’s internal functioning. Various stress hormones travel through the blood and stimulate the release of other hormones, which affect bodily processes such as metabolic rate and sexual function.

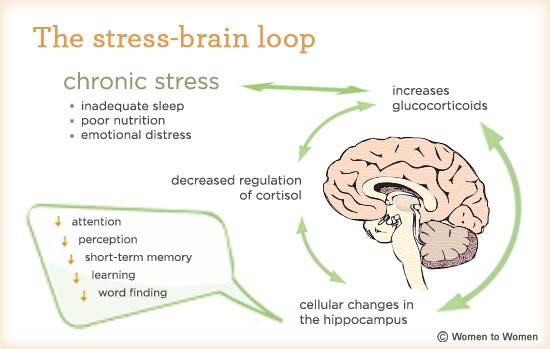

6The Role of Glucocorticoids In response to signals from a brain region called the hypothalamus, the adrenal glands secrete glucocorticoids, hormones that produce an array of effects in response to stress. These include mobilizing energy into the bloodstream from storage sites in the body, increasing cardiovascular tone and delaying long-term processes in the body that are not essential during a crisis, such as feeding, digestion, growth, and reproduction. Some of the actions of glucocorticoids help mediate the stress response, while other, slower actions counteract the primary response to stress and help re-establish homeostasis. Over the short run, epinephrine mobilizes energy and delivers it to muscles for the body’s response The glucocorticoid cortisol, however, promotes energy replenishment and efficient cardiovascular function.

7Glucocorticoids also affect food intake during the sleep-wake cycle. Cortisol levels, which vary naturally over a 24-hour period, peak in the body in the early-morning hours just before waking. This hormone helps produce a wake-up signal, turning on appetite and physical activity. This effect of glucocorticoids may help explain disorders such as jet lag, which results when the light-dark cycle is altered by travel over long distances, causing the body’s biological clock to reset itself more slowly. Until that clock is reset, cortisol secretion and hunger, as well as sleepiness and wakefulness, occur at inappropriate times of day in the new location.

8 Acute stress also enhances the memory of earlier threatening situations and events, increases the activity of the immune system, and helps protect the body from pathogens. Cortisol and epinephrine facilitate the movement of immune cells from the bloodstream and storage organs, such as the spleen, into tissue where they are needed to defend against infection.

9Glucocorticoids do more than help the body respond to stress They also help the body respond to environmental change. In these two roles, glucocorticoids are in fact essential for survival.